A recent phishing attack on GitHub

A couple weeks ago, I spotted a phishing campaign targeting developers on GitHub - actually, my coworker Max tapped me on the shoulder to show me. Phishing is nothing new, but this one caught my attention with the tactics, plus recent current events.

The attack used GitHub’s own features

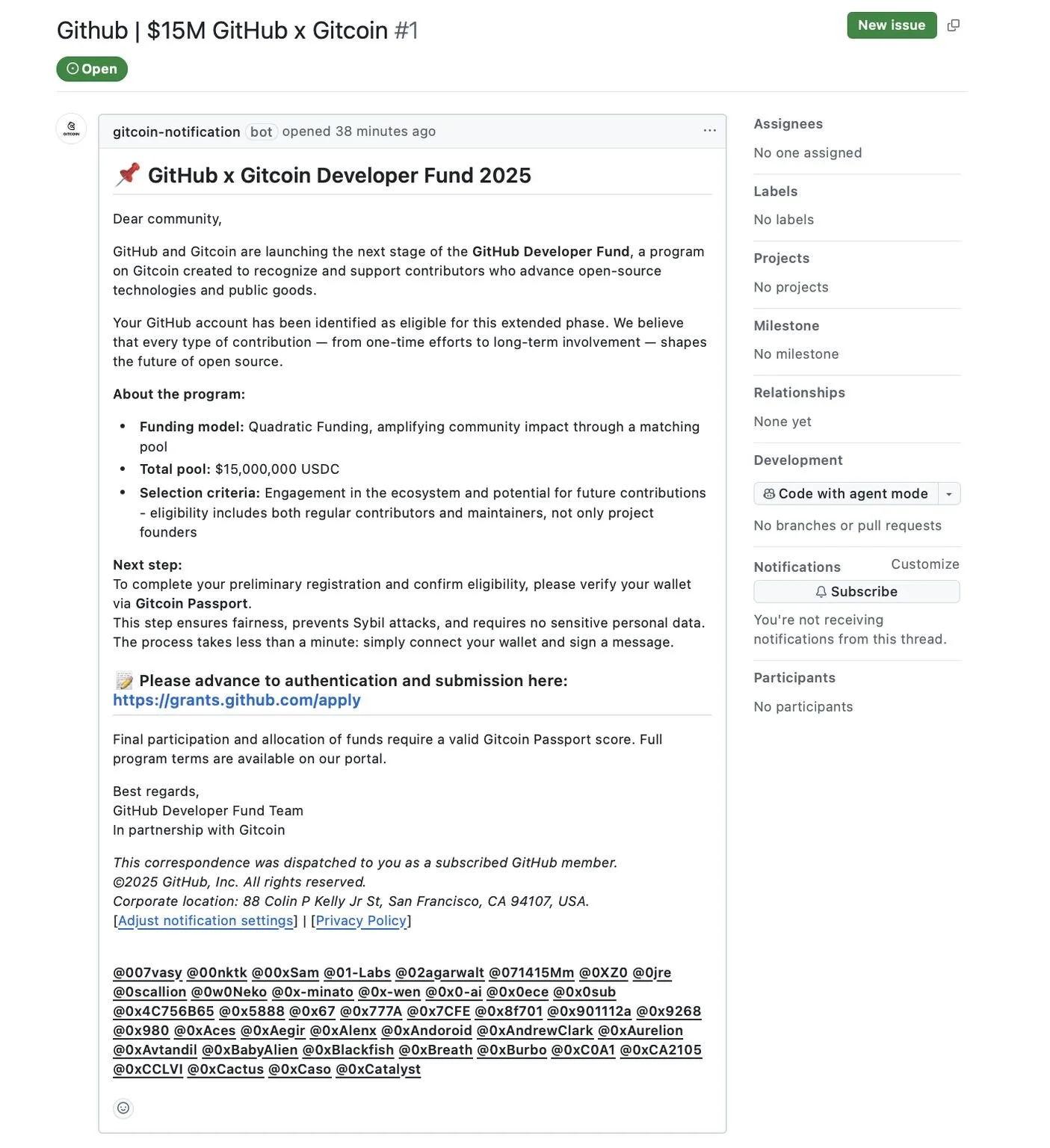

This was a clever social engineering attempt to reach open-source maintainers. In one form, it looked like this:

This isn’t convincing at all! What gives? At a glance, maybe it’s similar to the Microsoft research paper on why Nigerian scammers say they are from Nigeria:

By sending an email that repels all but the most gullible, the scammer gets the most promising marks to self-select, and tilts the true to false positive ratio in his favor.

Cormac Henley (Microsoft Research): Why Do Nigerian Scammers Say They are From Nigeria?

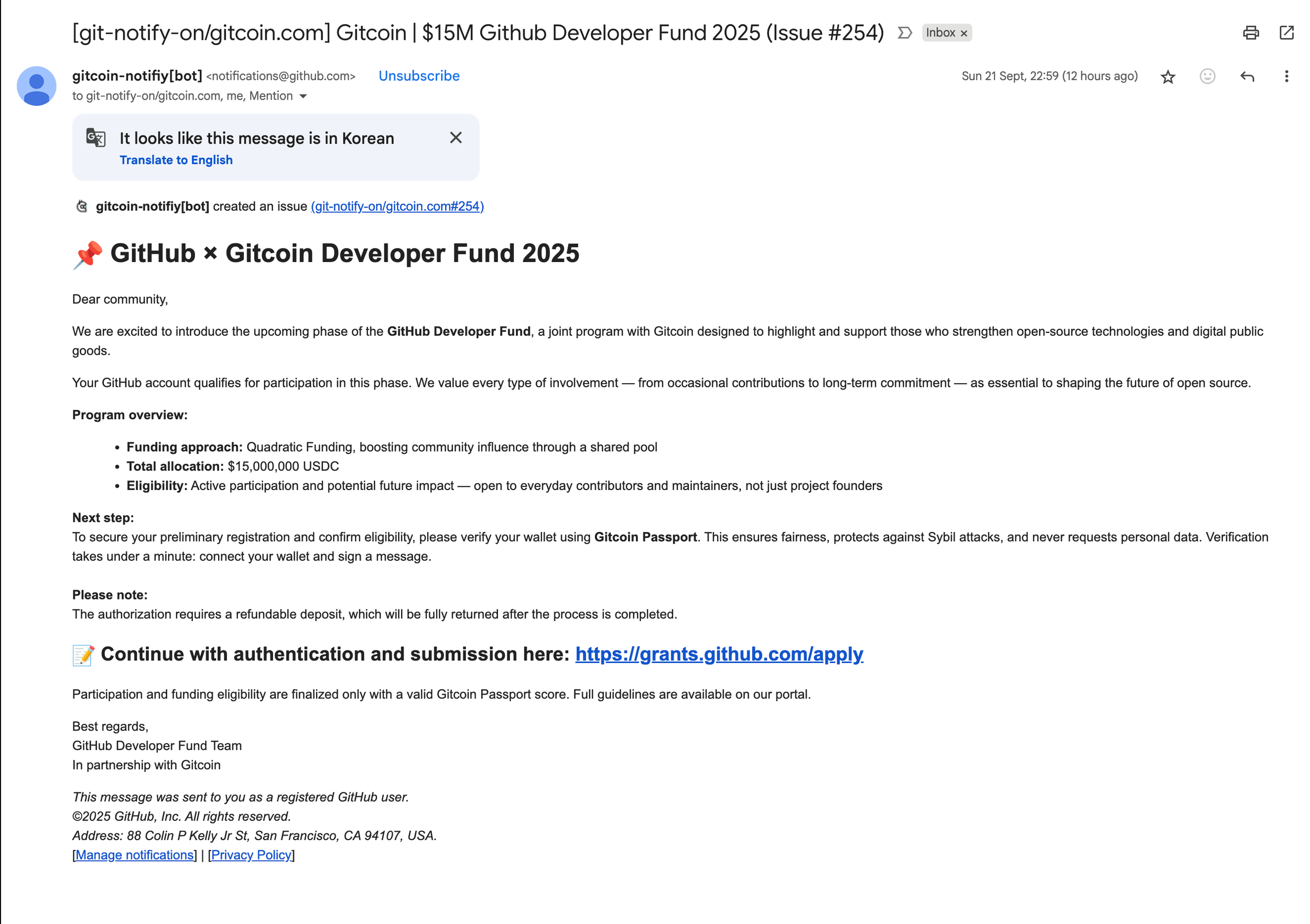

But if you were targeted, you wouldn’t see it in the Issues for a random GitHub repo. No, you’d see it in your email, like this:

A later GitHub issue from the same attack, in the form of an email notification. Image via Gitcoin forums.

Now we’re talking! It’s an email from an official Github address, has boring legalese at the bottom, and that giant list of tagged names isn’t visible anymore. It’s got the financial incentive to join, a plausible reason to log in, and what looks like a bare link (which actually points to the phishing site).

This is the kind of creativity I mean when I say: Every app is a messaging app. That’s why you see weird features like the ability to block people in Google Drive. Trust and safety teams deal with this all the time - it doesn’t matter if there’s no money at all involved on your website, as long as there’s a way to get a scam in front of someone’s eyeballs.

The GitHub security team took down the repo a few hours after we reported it, and played whack-a-mole with repeat attempts over the next few hours before quashing it. Notice in the email screenshot the app’s name has been changed to “notifiy” - a misspelling probably not due to carelessness, but intentionally to avoid a Reserved Username-style blocklist.

At the scale of GitHub, I can imagine you want to be careful about how broadly to do automated blocking, to ensure you’re not breaking issue creation or notifications for all of GitHub’s users.

Interesting times in software supply chain security

Just a few days before this phishing attack, 18 popular JavaScript packages were maliciously updated to steal cryptocurrency. Just a few days after the attack, the “Shai-Hulud” worm hit over 500 more packages to steal credentials.

I thought this was an interesting attack in that it targeted open-source contributors directly. Those contributors hold powerful credentials that can be used to publish malicious updates, and it can be easier to trick a human than it is to hack into package systems directly.

It’s telling that GitHub plans to deprecate time-based one-time passcodes (TOTPs), which are those rotating six-digit numbers that live in some app, and moving to FIDO-based 2FA, like WebAuthn passkeys and biometric authentication. This is explicitly an anti-phishing measure: TOTPs can be relayed, meaning the phishing site collects your current OTP and sends it to the real site; but in FIDO/WebAuthn, the credentials are associated with a specific domain - so your passkey or biometric auth won’t give away your (e.g.) GitHub credentials to some random phishing site.

—

JavaScript is notorious for vast dependency trees, but every language and ecosystem has libraries; the productivity of software engineers relies on standing on each others’ shoulders. As I wrote in the intro post of this blog, the combination of high-level programming languages and libraries makes everything easier; it’s as fundamental as interchangeable parts were to manufacturing.

I’ve seen some posturing on the internet from people saying these supply chain attacks are a reason to vibe-code your own utilities instead. But personally, I’ll take my chances with well-maintained and tested libraries.