What happens to your online accounts when you die?

A few months ago, I heard of a work acquaintance's death via his company's social media. Shocking and abrupt - I had just met up with him (let’s call him George) for the first time. We joked over beers in a cozy little alleyway cafe, me and a coworker and George.

It made me queasy to see George’s smiling LinkedIn profile photo, oblivious to the realities of flesh-and-blood. If you hadn’t seen the company announcement (which didn’t tag him), you might even still message him.

LinkedIn has a clearly-defined process for what happens to the accounts of the deceased, so I filed the support ticket: “Request to memorialize”, submitted to the bureaucracy of the living.

Within two hours, a support team member replied, “I'm sorry for not having a quick answer about your issue. I've forwarded your message to another group for additional review and advice.” No problem - I’m in no rush here. Over the next few days, my ticket bounced between a few more people; they asked me to re-file the ticket, and finally it was done.

At the end, the only thing to show for it was a new banner on the profile:

In memory of George

This account has been memorialized as a tribute to George’s professional legacy.

And beneath that one, the usual Sales Navigator banner gave me tips about selling to him. Somehow, I wasn’t sure any of our mutual connections would be able to help schedule a call with George.

“User-generated content”

The modern era of internet-based computing is so young that many of the original pioneers are still around. So what happens to those accounts and their data?

As we connect with each other online, we create “user-generated content”: public and semi-public comments, uploads, reactions, and more. These datapoints ripple out like waves. They travel far and persist long after the creator is gone - a digital wake, in both senses of the word.

Image transcription of a tweet: “A friend I loved very very much died a few years ago from cancer. She left up her GoodReads. I’m so glad because every few months when I’m looking up a book, I’ll find a review she left and her voice is so strong and funny and warm and I want to keep hearing it forever.”

In the physical world, a book review might have been published in a newspaper (if it was deemed worthy by the editors), and your descendants might be able to find it in public archives or your personal paper copy.

In the digital world, there’s an old saying: “Once it’s on the internet, it’s out there forever”. But in reality, huge swathes of the internet are not publicly reachable nor actively archived. Data is basically permanent, until the service provider decides otherwise; then, it’s suddenly gone.

Are the bits and bytes that make up our book reviews, photos, and short-form shouts into the void really so important? I say yes. These digital ephemera are part of our legacy.

The legal right to inherit digital assets

Some kinds of online accounts have clear policies. In your online bank accounts, the financial assets have a beneficiary; there is a well-defined legal process by which an individual inherits it. Data that lives in business tools like Microsoft Teams or Salesforce belongs to the company, and the remaining employees will inherit it as people leave. But many accounts, like social media, aren’t tied to cold, hard cash. They’re just a collection of bits living in someone’s database - and it might be inconvenient for that someone to grant you access.

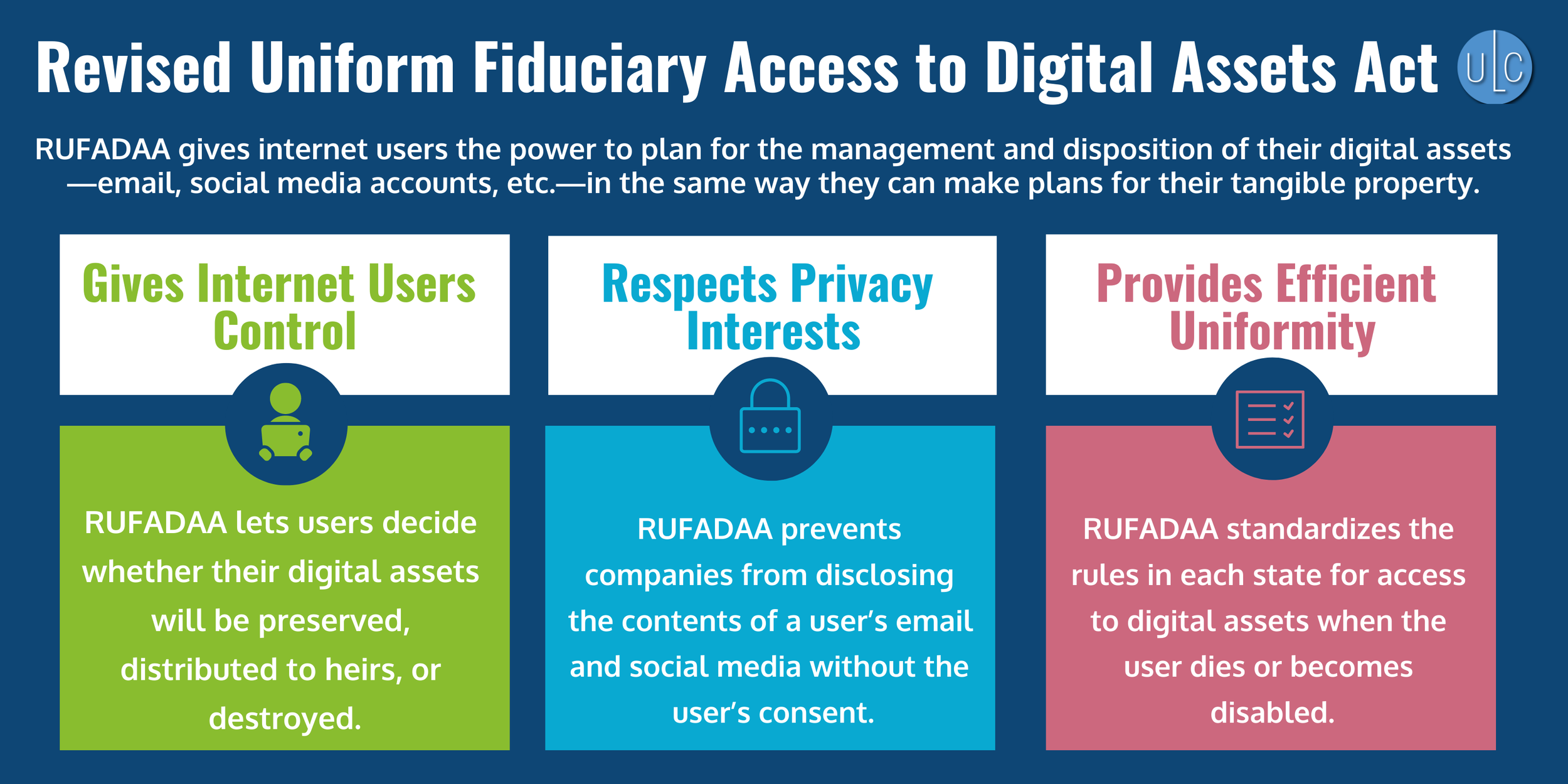

In the United States, it turns out there is established law about the inheritance of digital accounts and data: the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA), enacted in 49 states (and recently introduced as a bill in Massachusetts). It defines how a fiduciary (a person legally authorized to manage another person’s property) can access digital assets.

Infographic from the Uniform Law Commission, the nonprofit that drafted RUFADAA

RUFADAA defines default rules for how fiduciaries can access two categories of digital assets:

Electronic communications, like emails and other non-public messages between private parties

Content is private by default; a person must explicitly provide consent (while alive) for a fiduciary to access communications content, like email bodies or direct messages.

The catalogue may be accessed by a fiduciary; this is metadata that includes message senders, recipients, and timestamps. For example, a fiduciary might view that a particular bank emailed the deceased person monthly, and follow up directly with that bank.

Digital property, including photos and files in cloud storage, and fully-virtual currency like Bitcoin or video game currency.

A fiduciary can access all of this digital property.

You can plan for your digital assets through first-party management tools (like Google’s Inactive Account Manager or Apple’s Legacy Contact feature) or through traditional estate planning like a will. Otherwise, the service provider’s terms of service define fiduciary access; and finally if the ToS doesn’t say anything, the default RUFADAA access applies.

Once a service provider receives evidence of a fiduciary’s authority (like a court order), they can grant access to the fiduciary. A service can provide full or partial access to log into the account, or provide an export of relevant data.

This is a high-level summary; the full text of RUFADAA is worth the read if you’re curious about the details. I also found Michael D. Walker’s article on RUFADAA and digital estate planning provided helpful context.

I don’t have particular legal knowledge nor experience, but I do think RUFADAA maps well to how people intuitively want to think about their digital assets. You should be able to legally control them like physical assets. Private correspondence remains private under the default access terms. Props to the Uniform Law Commission for their work here, as well as service providers that create tools for users to manage their data legacy.

This law enables privileged access to the data of the deceased. But those accounts are still around - platforms need to decide how to handle them.

How we treat the dead

As I found out with George, memorializing a LinkedIn user causes a banner to be displayed at the top of his profile. Friends stop receiving birthday reminders, the deceased stops appearing in recommendations, and so on. It’s a thoughtful process, even if the support ticket flow wasn’t the smoothest - good hospitality from the LinkedIn team.

LinkedIn is among a select few sites that have a formally-defined process for dead users. Other major services with similar processes include Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Flickr, and GitHub. In lieu of a formal process, RUFADAA should get your fiduciary access to your data; but it might be easier if you leave behind a password manager or notebook with notable accounts and their login information - especially for end-to-end encrypted services.

Most inactive accounts probably belong to users who have lost interest, rather than passed away. Service providers will often prune inactive users’ data; I logged into my old Skype account recently to find no one online, and only empty histories in the old group chats (good, we were teenage boys then). Or, they might shift content policies like Tumblr and mass-delete entire subcultures. The ultimate annihilation of user-generated content happens when the service shuts down entirely, like GeoCities or Google+.

But a few of the juggernauts have persisted for two decades and will likely live on for decades more - the big email providers, Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube, and more. They will need to confront the challenges of dead users at greater scale.

They say all you needed to be remembered was one small stone piled on another, and wasn’t that what we were doing in the portal, small stone on small stone on small stone?

Patricia Lockwood, No One Is Talking About this

Today, our online accounts accumulate small stones, facets of our connected lives. In our lifetimes, we will see an ever-increasing number of online accounts representing the dead, each cairn frozen in time. One day, our own profiles will become a part of that landscape.

George’s memorialized profile says he’s a Director, he’s an Expert, he’s Strategic. He’s at the booth of a tech conference and wearing his glasses on his head. And I remember that alleyway cafe, and the sound of his laugh.

—

Do you have a story about the online accounts of someone who passed away? Reach out at bobbie@digitalseams.com .

—

Notable discussions:

2025-02-13 on Hacker News (67 comments)